2.3 Quadrilaterals¶

Our development of perpendicularity and triangles progressed well with no parallel condition, but attempting basic proofs about the properties of Euclidean quadrilaterals will lead us off the rails. We have reached the breaking point of neutral geometry.

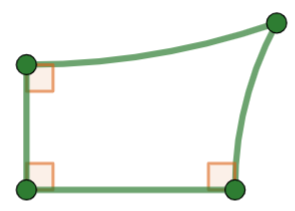

The problem is that, without a parallel postulate, there is nothing preventing geometric lines from having a slight curvature (see figure at right). If lines are not straight, the angle sums of triangles are not \(180^\circ\) and rectangles do not even exist.

Presenting the standard definitions of polygons and quadrilaterals will help us explore why our current structure is insufficient to guarantee Euclidean results.

- Polygon

A simple, closed curve comprised entirely of line segments.

- Quadrilateral

A polygon containing exactly four line segments.

- Parallelogram:

A convex quadrilateral with two pairs of parallel sides.

- Rectangle

A rectangle is a parallelogram with a right angle.

The Rectangle Quest¶

Two pioneers attempted to leverage the ideas of perpendicularity to prove rectangles exist without invoking Euclid’s Fifth Postulate: Giovanni Saccheri (1667 - 1733) and Johann Lambert (1728 – 1777).

As quests go, they both failed. However, their heroic quests both produced a great deal of geometric insight. Their investigations pushed neutral geometry to the brink of success.

Saccheri and Lambert both noticed what we found in the previous section: perpendicular lines and right angles behave quite well in a neutral geometry. They both created quadrilaterals with right angles to see if they could push through a proof that rectangles must exist even with no parallel condition specified. Lambert created a quadrilateral with three right angles and attempted to prove the fourth must be a right angle, too. Saccheri’s idea was to use two congruent sides both of which were perpendicular to a third side. The Saccheri quadrilateral was first used centuries earlier by Omar Khayyam, one of the earliest heroes to attempt the quest.

Saccheri knew that triangles having an angle sum of exactly \(180^\circ\) forced the geometry to be Euclidean, so he assumed the opposite. He quickly proved that, if angle sums were greater than \(180^\circ\), lines would have finite length which would contradict Euclid’s Second Postulate. Investigations into the assumption that triangles had angle sums less than \(180^\circ\) were much more fruitful and produced some of the earliest insights into hyperbolic geometry. Unfortunately, he also “proved” hyperbolic geometry was impossible, an ignominious ending to his brave quest.

Lambert’s attempt established an elegant result. The measure of the fourth angle of a Lambert quadrilateral corresponds to the parallel condition.

If the fourth angle is:

Acute

The geometry is hyperbolic

Right

The geometry is Euclidean

Obtuse

The geometry is elliptical

Lambert’s work in spherical and elliptical geometries helped him understand and produce projections from a globe to a two-dimensional map. He showed that triangles on curved surfaces like spheres and saddles do not have angle sums equal to \(180^\circ\). Like Saccheri, he proved several hyperbolic geometry theorems including that triangular area in hyperbolic geometry can be calculated using angle measure only.

- Saccheri Quadrilateral

A quadrilateral with two congruent sides, called legs, which are both perpendicular to a third side, called the base.

- Lambert Quadrilateral

A quadrilateral with at least three right angles.

- Summit

The line segment opposite the base of a Saccheri quadrilateral.

- Summit Angles

The angles in a Saccheri quadrilateral that are adjacent to the summit.

Theorems¶

The diagonals of a Saccheri quadrilateral are congruent.

The summit angles of a Saccheri quadrilateral are congruent.

The summit angles of a Saccheri quadrilateral are not obtuse and thus are either right or acute.

The line joining the midpoints of the summit and base of a Saccheri quadrilateral are perpendicular to both.

The summit and base of a Saccheri quadrilateral are parallel.

In any Saccheri quadrilateral, the length of the summit is greater than or equal to the length of the base.

The fourth angle of a Lambert quadrilateral is not obtuse, and is therefore either right or acute.

The measure of the side included between two right angles of a Lambert quadrilateral is less than or equal to the measure of the side opposite it.

The last chapter of the rectangle quest features Johann Bolyai and Nikolai Lobachevsky who, independently of one another, developed, explored and proved the theorems of non-Euclidean geometry.

Warning

Bolyai’s father, a mathematician named Farkas, begged his son to not pursue the quest at all.

You must not attempt this approach to parallels. I know this way to the very end. I have traversed this bottomless night, which extinguished all light and joy in my life. I entreat you, leave the science of parallels alone…Learn from my example” (emphasis added).

—Farkas Bolyai

Lobachevsky assumed Playfair’s Postulate was false and that, instead of unique parallels through a point for a given line, that multiple parallels were possible. He proceeded to develop and prove the theorems of hyperbolic goemetry and establish it as a logical and consistent system.

Bolyai’s discoveries overlapped Lobachevsky’s, but were significantly different. He developed the ideas of neutral geometry (sometimes called absolute geometry) along a similar path to the one we followed. He also established the ideas of non-Euclidean geometries. He published his work on hyperbolic geometry later than Lobachevsky, but independently, and he developed more general ideas of non-Euclicdean geometry.

Fig. 8 Visualizing the curvature of Euclidean, elliptic and hyperbolic geometry.¶

Bolyai wrote to his father, explaining the quest:

I have discovered such wonderful things that I was amazed…out of nothing I have created a strange new universe.

—Johann Bolyai

Gauss was already a rock star mathematician at the time Bolyai published his work. Gauss coined the term non-Euclidean geometry and told Bolyai that he had discovered hyperbolic geometry decades earlier but had not published his work. To a friend, after reading Bolyai’s work, Gauss offered a fine critique:

I regard this young geometer Bolyai as a genius of the first order.

—Carl Friederich Gauss

The quest concluded. Mathematicians had proved rigorously that Euclid’s Fifth Postulate was indeed a necessary axiom, and they further illustrated the three possibilities for geometries:

Euclidean geometry with unique parallels

Hyperbolic geometry with infinitely many parallels

Elliptical geometry with no parallels at all

Along the way, geometers learned the following ideas were all equivalent to the Euclidean parallel condition:

If the Converse of the Alternate Interior Angle theorem is true, the geometry is Euclidean.

If a rectangle exists, the geometry is Euclidean

If the angle sum of a triangle is \(180^\circ\), the geometry is Euclidean.

Tip

If the Pythagorean theorem holds for all right triangles, then the geometry must be Euclidean. This fact is not obvious but bears mention here.

Since each of these is equivalent to the Euclidean parallel postulate, they are also equivalent to each other. For example, if there exists a triangle with an angle sum of \(180^\circ\), then a rectangle exists. Or, if a rectangle exists, triangles have angle sums of \(180^\circ\).

Multiple lines through a single point parallel to blue line.

Multiple lines through a single point parallel to blue line.